The History of Goodison Park

The first purpose-built football stadium in England, and the only one to feature four double-decker stands.

Alex Young (speaking with Becky Tallentire): "Goodison Park to me just seems to be a magical place, it's like when you go into certain houses where the great ghosts have been. There was something there that made the back of my neck tingle when I ran onto the pitch for Everton, even when the place was empty.

"It's still the same whenever I go down, that feeling is still there – home matches especially, you could feel the vibes from the fans. I loved playing at Goodison and that's why the majority of the games when I turned it on, it was at home. I could feel the goodwill coming from the fans.

"I felt it again in February 2000 when I was down for the Millennium Presentation, I won an award and my wife, Nancy came on the park with me and she said it made her Millennium – it was the greatest thrill she's ever had, going on the pitch with a 35 or 40,000 and every single one of them wishing us well, we could both feel the vibes. For me it's a magical place, the best place I' ve ever played football and I'll never, ever forget it."

¤ ¤ ¤

¤ ¤ ¤

Were it not for an escalating series of disputes between Everton and their landlord at Anfield, John Houlding, Goodison Park, the Toffees’ iconic and history-laden old stadium, might never have been built. Finally taking umbrage at Houlding’s decision to more than double the club’s rent at Anfield by early 1892, George Mahon and the Everton board made the fateful decision to take the core of the club and find land for a new ground, eventually settling on the Mere Green field.

Left with a stadium but no team, Houlding, a local alderman and Conservative MP, formed a new club, attempting to register it as Everton FC and Athletic Grounds Ltd., a name rejected by the Football Association, before choosing Liverpool FC, thereby creating one of English football’s most enduring rivalries.

Meanwhile, the original Everton – indeed, the City’s original team – soon named their new site on the other side of Stanley Park after the road that ran alongside it (which itself had been named after local civil engineer, George Goodison) and embarked on a project that would result in England’s first ever modern stadium, purpose-built for football and which would remain at the forefront of the English game for the next century.

It would become Everton's fourth home in 14 years. Originally formed in 1878 as St Domingo FC when they played on Stanley Park opposite Houlding's house, the club moved to nearby Priory Road once it became clear that the rising number of spectators attending matches would require a fenced and gated pitch if the club wanted to charge admission.

Within two years, however, club president Houlding had secured land on Anfield Road and Everton moved again to the location where they would win their first League title in 1891, before moving across Stanley Park once more in the wake of the schism in the club that occurred the following year when Houlding raised the rent from £100 in 1888 to £250 a year after the championship triumph.

The Everton committee, now based in the Sandon Hotel, rejected Houlding's offer to sell Anfield to them for £6,000 and ended up taking up the option that Mahon had on the plot at Mere Green, described in 1906 by Gibson and Pickford's Book of Football as having "degenerated from a nursery into a howling desert", for £8,090. It was more than they might have paid to stay where they were but it bought them freedom from Houlding.

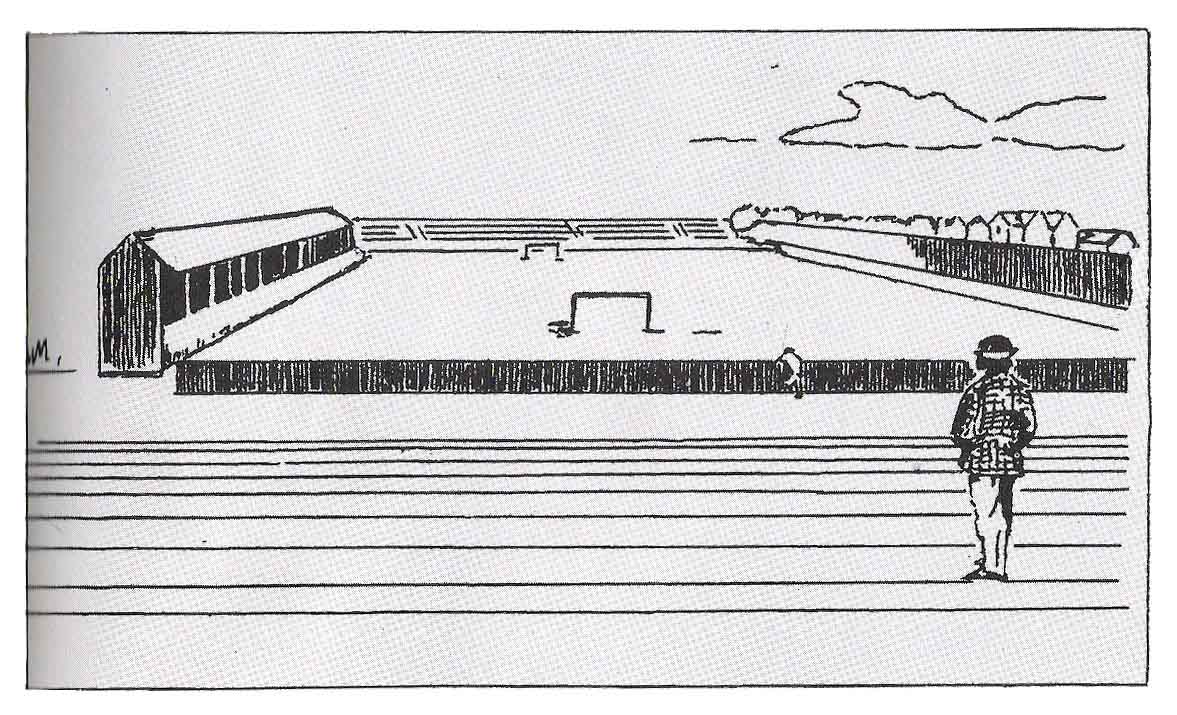

Once cleared of debris, levelled, drained and sodded, construction of two uncovered stands and one covered stand was begun at Goodison Park by Walton contractors, Kelly Bros.

The first known sketch of Goodison Park

As Simon Inglis described in The Football Grounds Of Great Britain:

"Everton performed a miraculous transformation at Mere Green, spending up to £3,000 on laying out the ground and erecting stands on three sides. For £552 Mr. Barton prepared the land at 4½d a square yard. Kelly Brothers of Walton built two uncovered stands each for 4,000 people, and a covered stand seating 3,000, at a total cost of £1,460. Outside, hoardings cost a further £150, gates and sheds cost £132 10s and 12 turnstiles added another £7 15s to the bill.""

By August, the new stadium was officially opened with a brief athletics meeting, a selection of music and a fireworks display, and on 2nd September, 1892, she played host to her first match, a keenly-contested friendly against Bolton Wanderers which Everton won 4-2. Wolves's Molineux had opened three years earlier but was far less developed than Goodison Park; likewise Newcastle's St James's Park. As Inglis wrote, "Only Scotland had more advanced grounds. Rangers opened Ibrox in 1887, while Celtic Park was officially inaugurated at the same time as Goodison Park."

In October 1892, Out Of Doors effused:

"Behold Goodison Park!...no single picture could take in the entire scene the ground presents, it is so magnificently large, for it rivals the greater American baseball pitches. On three sides of the field of play there are tall covered stands, and on the fourth side the ground has been so well banked up with thousands of loads of cinders that a complete view of the game can be had from any portion."

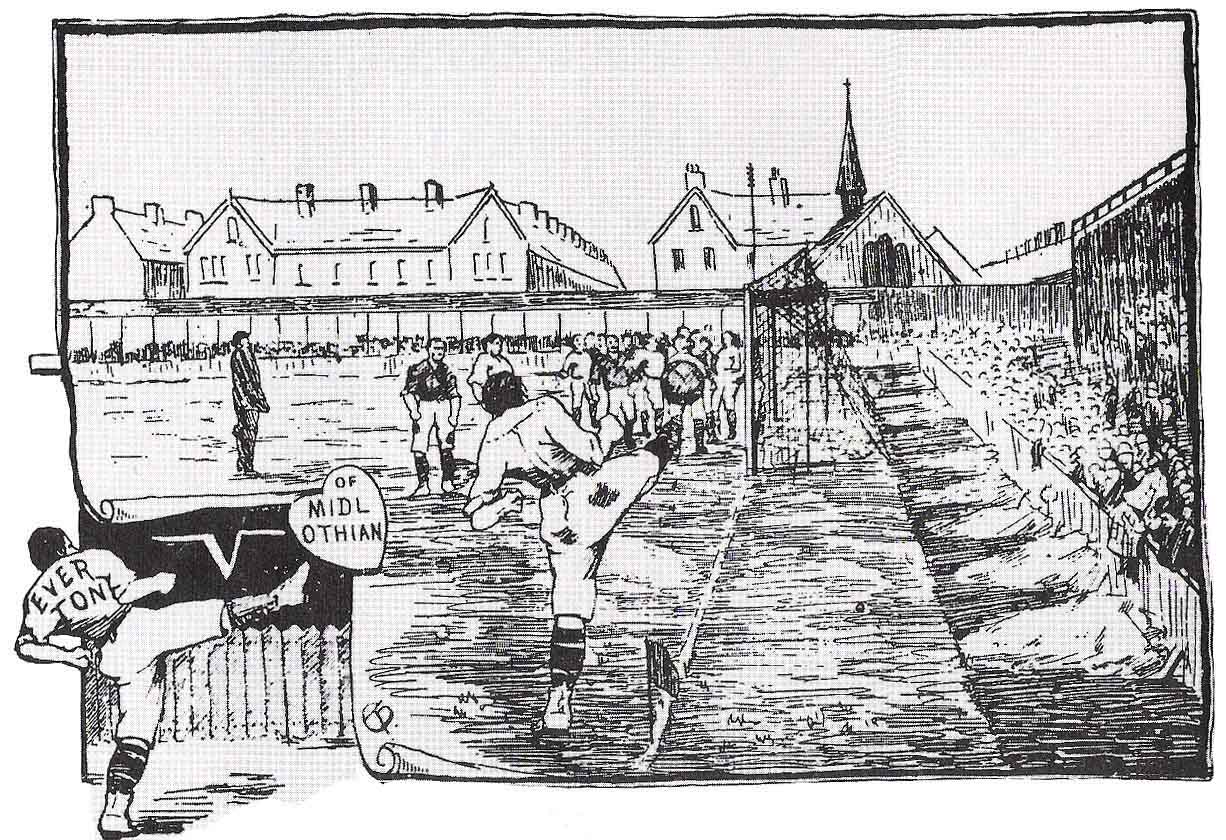

An early sketch of a match from 1892 showing the Gwladys Street stand

Below, extracts taken from "The Football Grounds Of Great Britain" by Simon Inglis, brought to you by Mike Southworth, and updated since 1987 to include the Park End Stand, built in 1994.

A year after moving, Everton were FA Cup finalists in 1893, then runners up again in the first Division in 1895. The ground was honoured in 1894 when Notts County beat Bolton in the FA Cup Final, watched by a disappointing crowd of 37,000, but everton were still the richest club in the country, and League gates such as the 30,000 which attended in February 1893 were still regarded as enormous.

Despite the initial developments, it was not long before Goodison Park was improved even further. A new Bullens road Stand was built in 1895 at a cost of £3,407 (although the original construction seems to have been more than adequate, unless the work involved only spectator facilities) and the open Goodison Road side was covered for £403.

Meanwhile competition in the city was reaching peak levels. Everton were again runners up in both the League and FA Cup, while across Stanley Park, Liverpool won their first Championship in 1901.

The Goodison Park of today really began to take shape after the turn of the century, beginning in 1907 with the building of the hideous and far too small Park End double-decker stand, at a cost of £13,000. It was designed by the club's architect, Henry Hartley, and the club would have lost problems with it subsequently. In 1909, the old large Main Stand on Goodison Road was built. Costing £28,000 it housed all the offices and players' facilities, and survived until 1971.

At the same time another £12,000 was spent on concreting over the terracing and replacing the cinder running track. The "Athletic News'" correspondent wrote in the summer of 1909, "Visitors to Goodison Park will be astonished at the immensity of the new double-decker stand". The architect was Archibold Leitch, and the front balcony bore his criss-cross trademark, which can still be seen on the Bullens Road Stand opposite, and was also a feature on the main stands at Ibrox and Roker Park for most of the 20th Century, until these grounds were modified or abandoned.

In recognition of the fact that the ground was by far the best equipped in England, Everton hosted the 1910 FA Cup Final replay between Newcastle and Barnsley. On this occasion 69,000 attended. Then on 13 July 1913, Goodison Park became the first League venue to be visited by a ruling monarch, when George V and Queen Mary came to inspect local schoolchildren at the ground.

During the First World War, Goodison was used by the Territorial Army for drill practice. Soon after, the US baseball teams Chicago White Sox and New York Giants played an exhibition match at the ground. One player managed to hit a ball right over the Main Stand.

The next major development took place in 1926, when at a cost of £30,000 another double-decker, similar to the Main Stand, was built on the Bullens Road Side opposite. Again, Leitch was the architect.

In the 1930's Everton borrowed an idea from Aberdeen FC, who they had visited for a friendly. At Pittodrie in 1931, trainer Donald Coleman had built the first ever dug-outs in the country, and probably the world. Not only did Coleman want shelter on the touchline, but also a worm's eye view of his players' footwork. From Pittodrie and Goodison Park the idea soon spread, and now the covered dug-out is a feature of almost every ground

Another Royal visit occurred in 1938. George VI and Queen Elizabeth, the present Queen Mother, came to Everton and saw the new Gwladys Street Stand, just completed for £50,000. Notice how costs had escalated over the years. Goodison Park thereby became the only ground in Britain to have four double-decker stands and was newly affirmed as the most advanced stadium in Britain. Some writers referred to it as "Toffeeopolis", after the club's nickname.

Goodison Park suffered quite badly during the Second World War, because it lies so near the Liverpool docks, and the club received £5,000 for repairs from the War Damage Commission. Shortly after the work was completed, Everton enjoyed their highest ever attendance, 78,299 for the visit of Liverpool in Division One, on 18 September 1948.

Floodlights came to both Liverpool clubs in October 1957. The Goodison Park set, which were originally mounted on four extremely tall pylons, were switched on for an Everton v Liverpool friendly on 9 October.

A year later the club spent £16,000 installing 20 miles of electric wire underneath the pitch. The system melted frost and ice most effectively, but the drains could not handle the extra load, so in 1960 the pitch was dug up and new drainage pipes laid.

The 1960s, like the 1930s saw Everton win the Championship twice and the FA Cup once, and in 1966 Goodison Park attained its peak of fame and fortune, staging five games in the magical World Cup, including group matches for Brazil and a hugely memorable quarter-final between North Korea and Portugal. No other English venue apart from Wembley staged so many World Cup games.

In preparation for the World Cup, the club had bought and demolished some of the Victorian terraced houses which stood behind the Park End Stand, in order to make a new entrance way from Stanley Park. The houses had originally been built by the club for players, and Dixie Dean had lived in one of them.

The next and (still) perhaps the most spectacular development was in 1971, when the 1909 double-decker Main Stand on Goodison Road was demolished to make way for a massive new three-tiered Main Stand. The old stand had cost £28,000 and was then considered immense. The new stand cost £1 million and was nearly twice the size, and was the largest in Britain until 1974, when Chelsea opened their mammoth East Stand, which cost twice as much and nearly brought financial ruin.

Because the Goodison Road Stand is so tall, the floodlight pylons were taken down and lamps put on gantries along the roof. The old-fashioned Bullens Road pitched roof was replaced by a much flatter modern roof and similar gantries installed there also. Anfield's lights followed the same pattern a year later.

When the Safety of Sports Grounds Act came into effect in 1977, Goodison Park's capacity was greatly reduced from 56,000 to 35,000, mainly due to outdated entrances and exits. So Everton had to spend £250,000 in order to reach a capacity of 52,800. The 1986 figure stood at 53,419, of which 24,419 were seated.

In the early 1980's the original corrugated roofing of the Gwladys Street Stand was replaced by blue cladding, giving the roof a rich colourful hue. Then, in 1987, the pitched roof was replaced by an upturned sloping roof extending out over the terracing below, which joined the roof of the Bullens Road, creating a continuous roof on two sides of the ground.

The next development was the conversion of Goodison to an all seater stadium, following the Taylor Report, in the aftermath of Hillsborough. This invoved seating the paddock, enclosure and Gwladys Street terracing. The Park End terracing remained but was only opened for big games. The reason for this was the intended redevelopment of the Park End. This came to fruition in the early part of 1994. The last time spectators stood on the terrace was on 19th January at the FA Cup 3rd Round replay against Bolton. The old stand was pulled down during February, with construction beginning soon after. The new stanley Park End Stand is a single tier cantilever stand with a capacity of 6,000. It also houses new facilities such as the Football in the community Scheme and the Supporters Club. The stand was opened on Saturday 17 September 1994 by David Hunt MP. A contribution of £1.3M was also given by The Football Trust.

The completion of the Park End brought Goodison Park's capacity up to 40,100, a figure exceeded by only the projected capacities of Old Trafford and Anfield, neither of which are in such a confined area as Goodison Park.

The next step will more than likely be to replace the wooden seats which remain in the Lower Bullens Stand and in parts of the Main Stand, bringing Goodison Park right up to date and back to its rightful place as one of the best stadiums in Britain.

Ground Description

Anfield, at the top of Stanley Park, is a solid mass on the skyline while Goodison Park, at the foot of the gentle slope, is a gaunt cathedral among low terraced houses. Two such important clubs, so close, yet seemingly turning their backs on each other across the green expanse.

Goodison Park is difficult to see from street level, not merely because it no longer has those giant floodlight pylons. The tall Main Stand does not at first look like a football stand, but part of a factory or brewery perhaps. The main entrance is on Goodison Road, where on one side is an unbroken line of terraced houses, small shops and The Winslow public house, on the other the high wall of the stand. There is no room for a gate or a courtyard. Above the doors and windows are a succession of signs, pointing here and there, telling you where you are or how you can get to where you should be; one of those admirable grounds that likes to keep its public informed and does not assume that everyone is a regular.

Inside, the stand seems titanic. The front section, originally for standing, now houses the Family Enclosure, and is in part backed by a line of executive boxes. These were a later addition, similar to those at St Andrews or Portman Road. When the stand was built, the club either saw no demand for this kind of accommodation or were unable to afford them – Manchester United had built boxes earlier – so they have had to add boxes in a way which detracts from the original design of the stand. The middle tier houses, among others, the Directors Box, sponsors and their like, above which is the upper tier – The Top Balcony.

Unfortunately, because of the angle of Goodison Road, at the end closest to the Park End the back wall angles in towards the pitch, and creates the illusion that the stand is somehow falling down, because the top tier of seats falls away, row by row, into the corner in a most alarming way. Since the building of the new Park End Stand, these seats are not used because the roof extends out under the Main Stand roof and blocks the view of the Park End goal.

At this corner, between the Main Stand and the Park End is a tall rectangular block, clad in blue. It houses stairways vital for safety in such a large stand, but has the additional and detrimental effect of closing off that corner in darkness. The opposite end is much more impressive. A large expanse of glass pannelling is dramatically cut in half by the sloping rake of the Top Balcony, apparently suspended in air. Notice at the front the very compact dug-outs, and the barely visible players' tunnel in between.

This dominating, but scarcely attractive structure seats 10,155 in the upper tiers alone, more than the total capacity of several grounds in the lower divisions, plus 12 private boxes and the seating in the Family Enclosure.

From here, look down to the left to Goodison Park's most famous landmark, the church of St Luke the Evangelist. The church presses so far into the ground that its walls are just feet from the stands. Everton once tried to pay for its removal in order to gain extra space, but had they succeeded, a familiar landmark would have been sorely missed.

As it is, this corner is the most open of all. On the left is the Gwladys Street End, similar to the two ends at White Hart Lane, with a balcony frontage distinguished by thin blue vertical lines along white facings. The terracing held 14,200 before the seats were put in to comply with the Taylor Report, and it once had a distinctive crescent wall setback nearest the goal to prevent missile-throwing incidents. This would be a familiar sight to anyone who has seen the games played there during the 1966 World Cup. The roof extends out over the Gwladys Street Stand and joins the Bullens Road Stand roof in the opposite corner.

The Bullens Road stand, opposite the Main Stand, is in three tiers, the rear section of the terracing having been converted to form the Lower Bullens Stand some years ago. The old terracing in front has now gone too, replaced by seating post-Hillsborough. There is seating for 8,067 on the two levels, with the section closest to the Park End now used to house away fans from top to bottom. Notice particularly the distinctive balcony frontage, criss-crossed with blue steelwork on a facing of white wooden boards — a distincive trademark of Archibald Leitch. The seating in the upper tier, now much less gloomy with the up-turned roof, has the name "EVERTON' picked out in white seats among the blue.

The Park End Stand is the newest of the four, built in 1994. It differs from all the others in that it is a cantilever stand with only one tier of seating, compared to at least two in all the others. It seats 6,000 from pitch level up to a height matching that of the seats in the Upper Bullens Stand, with space in front for wheelchair-bound supporters. The electronic scoreboard is suspended beneath the roof, visible from everywhere in the ground except the Park End.

The Park End stands on its own, not physically joined to either the Bullens Road Stand or the Main Stand. It's roof level, however, meets that of the Bullens Road roof giving a sense of continuity to three sides. The gap between the Bullens Road Stand and the Park End allows air to flow over the pitch, helping to maintain one of the best playing surfaces in the country, and also provides Sky Sports with somewhere to build a temporary studio for televised games.

Goodison Park still has all the hallmarks of a fine stadium, and although it can no longer claim to be the most advanced in the country, it is certainly one of the best equipped. It has none of the grandeur or impression of space experienced at Hillsborough or Highbury and suffers from being hemmed in. Nevertheless, perhaps because of its crucial place in the history of football and football grounds, and the atmosphere which prevails here on special occasions, Goodison Park is still one of the best grounds in Britain. "Toffeeopolis" lives on!

The Future

In thye summer of 2021, Everton broke ground on a new stadium on the banks of the royal blue Mersey at Bramley-Moore Dock many years after the club had determined that redevelopment of Goodison Park to the required capacity wasn't feasible on its "landlocked" footprint. That decision sparked the Great Stadium Debate and a number of alternative solutions before, under the ownership of Farhad Moshiri, the north docks was finally selected.

Under Moshiri and the Club's proposals, its iconic home of more than 13 decades would be replaced by the Goodison Legacy Project aimed at providing a range of community assets in Walton.