Rebuilding Goodison

This is an extended version of the first article, with some familiar background material, some thumbnail sketch plans and a few inner-city alternatives. Some have written in to question the technical and practical issues. However, I am only urging Everton to learn from the examples of Manchester United and Newcastle United (adding a bit more style), both of whom built their clubs (along with their fan-bases) using the patient and energetic application of good business principles during the 1990s, rather on the gamble of a single ‘big bang’. I have wide experience of major projects and would not put anything forward that wasn’t realistic. However, I am suggesting a patient high-quality long-term alternative to the one-off cheap-and-cheerful quick fix of Kirkby.

1. The Problem

Everton Football Club is one of Liverpool’s great cultural assets and Goodison Park is an internationally-famous landmark. However, many supporters don’t attend games as often as they might because of the restricted capacity (40,000), the obstructed views and the poor quality of the accommodation. Nevertheless, the atmosphere during the games is often very good and the ground and its setting embody a fascinating history. For Everton FC to move forward, the facilities need to be radically improved and the capacity needs to move towards 60,000, without sacrificing any of the positive aspects of history and atmosphere.

2. An Assumption

The City of Liverpool has a unique heritage of internationally recognised inner-city landmarks, including the waterfront, the two cathedrals, theatres, museums and galleries, and the two football grounds. Every effort must be made to retain all of these assets within the inner city, and develop this inheritance to attract visitors and economic activity. This is surely a priority for the City of Liverpool, in its role as a regional focus for much of North-West England and North Wales. No ‘out-of-town’ development, whether in Kirkby, Speke, or on the Wirral, could match the centre’s regional focus.

3. The Solution

This article describes two ways forward. The first, and preferred approach, is to develop Goodison Park and contribute to the long-term regeneration of the surrounding streets. The second approach is to identify a new site for a 60,000-seat stadium, with associated commercial opportunities, within inner-city Liverpool. Five options are put forward for each approach. All would require the active support of the City Council (as has been given to Liverpool in their proposal to build within Stanley Park), in providing a sustainable development framework, which both supports the development and at the same time protects the existing community and prevents planning blight.

4. Background

Anfield was the early home (between 1884 and 1892) of Everton Football Club, one of the twelve founding members of the Football League. Everton have played more seasons of top-flight football than any club in England; they have won the title nine times and held the trophy during both world wars.

An argument with the landlord led to Everton moving out of Anfield and building England’s first major football stadium on the other side of Stanley Park. Goodison Park was opened in 1892, and a new club, Liverpool, was founded to play at the vacated ground. Thus, the close proximity of the two clubs is not an accident and it can be argued that the special rivalry between them has been a catalyst to their each enjoying long periods of success, and bringing income and prestige to the city.

In 1966, Goodison Park was deemed to be the best club ground in England, and among the best in the World. Consequently it hosted one of the World Cup semi-finals (the other being at Wembley). However, subsequent improvements to the ‘old lady’ have been limited to those necessary to comply with changing regulations (such as the introduction of seating in all parts of the ground). The capacity is barely half what it was and standards have fallen behind those of many of its rivals, in England and elsewhere.

Everton are at present sixth in the Premier League. In recent times, they have fallen behind three other clubs (Manchester United, Arsenal and Liverpool), in terms of both overall trophy wins and commercial performance. Somewhat belatedly, the club have come to see stadium development as a pre-requisite to future success. However, the present position should not be talked down; the club is not broke and it is well-placed to begin a phased re-construction, financed in the usual way as part of an expanding business. All but a very few clubs would envy Everton’s position.

5. The Context

Stanley Park is one of a string of fine Victorian parks in the inner-city. It shares the characteristics of Princes Park, Sefton Park, Birkenhead Park, Newsham Park and others in containing ornamental lakes and planting as well as a range of historic structures. A few of the typical villas and large terraces that helped to fund these Victorian parks survive along the south side of Stanley Park. To the south-east and to the north-west, areas of traditional terraced housing survive (in Anfield and Walton respectively). To the north of the park is the large and equally historic Anfield Cemetery. However, the environment along Walton Lane is poor and in need of new development, to a scale that would re-establish the sense of urban enclosure on the west side of the park.

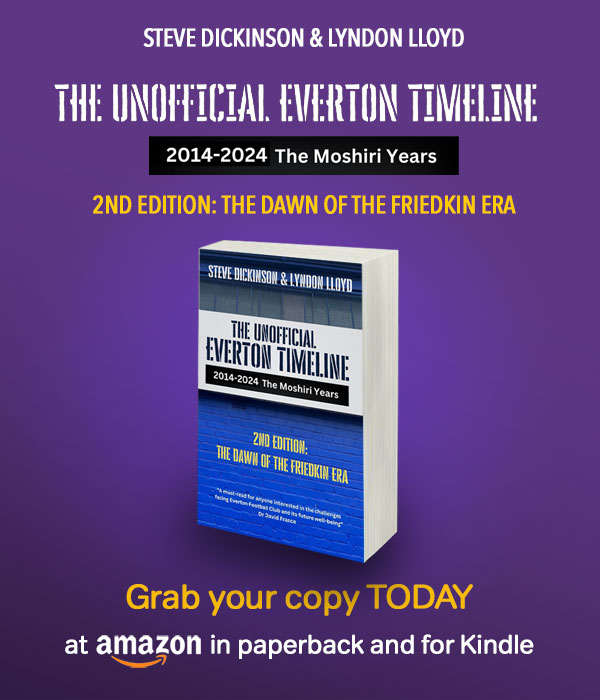

Despite the neglect and erosion of its historic character, this still constitutes a valuable historic cityscape, which is not beyond repair. The presence of two of the world’s most famous football clubs gives it a unique international profile and this could be the catalyst for an upturn in the area’s fortunes.

6. Previous Proposals

Both Everton and Liverpool have sought to expand their existing sites over the years. The re-developments of the Park End stand at Goodison and the Centenary Stand at Anfield both made use of space gained by the purchase of adjoining houses. However, the lack of an appropriate strategic plan (which would have recognised the long-term importance of the two football clubs within their respective communities) has led both of them to look for alternatives.

Occasional talk of a shared stadium (including a proposal for a 67.000-capacity stadium at Aintree) has met predictable hostility from many supporters of both clubs. By the late 1990s, Everton had enquired about the possibility of building in Stanley Park and were looking at a number of other sites around the edge of the city.

7. Kings Dock and the New Anfield

The Kings Dock proposal seemed to be an idea whose time had arrived. The city lacked a 10,000-seat arena of the type that had appeared in Birmingham and Manchester, and the success of the multi-purpose Millennium Stadium in Cardiff had sown the seeds of an even more impressive project for the Kings Dock. Such an ambitious venture would require a regular tenant (an equivalent of the Welsh Rugby Union). Everton refused an offer of tenancy, but after a thorough competitive process a proposal emerged, based on shared ownership between Everton FC and several public bodies. The architects of the Millennium Stadium (HOK) had drawn up an arena with a variable capacity (from 55,000 down to 15,000), a sliding roof and a sliding pitch (allowing the grass to grow outdoors).

However, defeat was snatched from the doors of victory. The club were reluctant or unable to put their seal on the agreement and, in the face of an urgent timescale imposed by the award of European Capital of Culture 2008, the City Council decided to go ahead with a smaller and more conventional arena, allied to a conference and exhibition centre.

In the meantime, against the background of the extraordinary offer being made to Everton and in the interests of ‘fairness’, Liverpool were given permission to build a new stadium in Stanley Park, something that in normal circumstances would have been unthinkable. Then, after the collapse of the Kings Dock proposal, in an attempt to re-balance the position, there were renewed calls from some quarters (notably the various public bodies involved) for the clubs to share the New Anfield. But this won’t happen; Liverpool are looking ahead with new confidence and Everton are feeling that they have been left ‘high and dry’. The history books may show otherwise, but the general perception is that the City Council is favouring Liverpool at the expense of Everton.

The Lure of Kirkby

While Liverpool City Council appears luke-warm, Knowsley Council is grabbing the opportunity to try to bring major new investment and long-term visitor potential to Kirkby town centre. Kirkby was built to house many of the people who were cleared from Everton and other inner city areas in the 1950s and 1960s. And Everton’s theme tune is Z-Cars, from a television series that was based in the ‘new town’ of Kirkby. The

proposed new stadium would ‘anchor’ a major new development, by Tesco, whose Chief Executive, Sir Terry Leahy is a well-known Evertonian and an advisor to the club.

Notwithstanding the above, the proposal would tear Everton away from its inner-city roots, it would tear it away from its historic rivalry with Liverpool FC, and it would place the club in an ‘out-of-town’ environment at a time when the city centre is re-establishing itself as a regional, national and international focus for visitors.

The ‘clearance’ of the inner-city in the 1960s and 1970s, and the consequent loss of population, drained much of the life-blood from Liverpool and led to the decay of much of the remaining heritage. At one time, it might have seemed inevitable that cultural and commercial activity would join this flight to the suburban fringe, but the policy of large out-of-town commercial developments has been discredited, in favour of consolidating historic centres. Across Europe and North America, the idea of the out-of-town stadium in the middle of a car park has given way to rebuilding in the inner-city or within the city centre.

9. Social and Industrial Heritage

We ‘know our history’ and the importance of Everton in the history of World football. Sometimes, the towering stands, surrounded by a tight community of terraced streets, remind me of communities such as Saltaire in Bradford, where the Victorian mill and surrounding terraced streets have been designated a World Heritage Site. The Textile Mill and the Football Stadium are comparable developments of the industrial revolution and the genesis of modern social management, and the finest examples of each are worthy of care and preservation.

The two original stands at Goodison Park (Bullens Road and Gwladys Street) have been diminished by the addition of metal cladding and advertising boards, but a good case could still be made for these structures to be given listed building status and restored accordingly (and integrated into a sensitive modernisation and expansion of the stadium). The historic streetscape of Goodison Road, Gwladys Street and the area around St Luke’s Church could become the core of a large Conservation Area, which would give the community confidence in the long-term future, at a time when some terraced housing in Liverpool is, once again, facing the spectre of ‘clearance’.

10. Experience Elsewhere

10a. The Community Ballpark: Chicago Cubs & Denver

Wrigley Field, home of the Chicago Cubs, is an icon in ‘ballpark’ circles. Simon Inglis devotes a chapter to ‘Wrigleyville’ in his book ‘A Stadium Odyssey’. This should be required reading for anyone who doubts the potential for a historic ground (like Goodison Park) in an inner-city area to prosper as the heart of its community as well as being a magnet for the wider region. He writes: “...and the best way for a community to feel at home with its stadium is for the stadium operators to embrace, and to respect, the local people and make them feel proud of the extraordinary building in their midst. It’s a two- way thing...”

The Coors Stadium in Denver is a good example of the new breed of American stadia that are being constructed in city centres to take advantage of the synergy between the stadium and other city centre facilities, including accessibility and transport.

10b. Inner City Football: Athletic Bilbao & Monaco The San Mamés Stadium (‘La Catedral’) in Bilbao is the ultimate example of an inner- city football club, which is at the spiritual heart of its city and region. Its tight urban site is in many ways comparable to Goodison Park, although closer to the city centre.

The Stade Louis II in Monaco is an extraordinarily luxurious building at the heart of this high-density principality, directly below the cliff-top Royal Palace. The stadium covers the fourth floor of a city block, with shops, offices, a swimming pool and a multi-storey car park below pitch level.

10c. City Centre Stadium: Newcastle & Cardiff

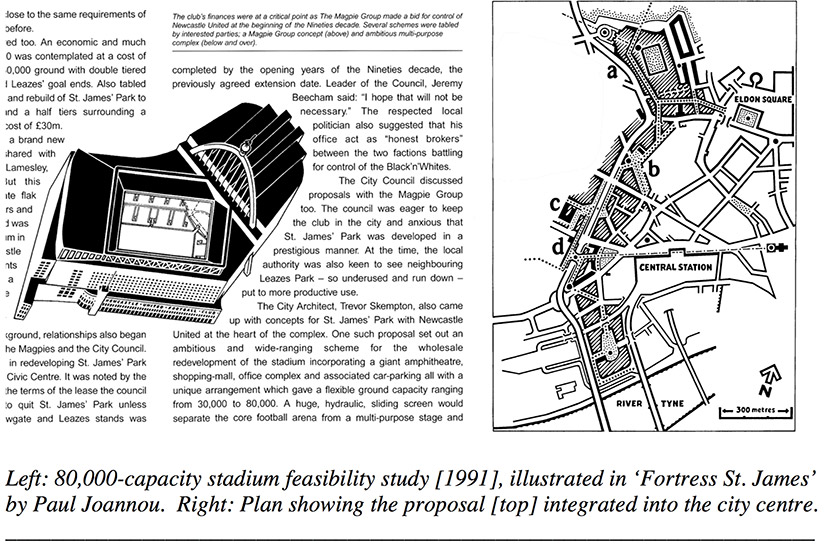

In the early 1990s, Newcastle City Council had to work hard to persuade Newcastle United that their future was in the city centre, rather than out-of-town or across the river in Gateshead. At the time of the Taylor Report, the Toon were at a low ebb, near the bottom of the (former) Second Division with a capacity of less than 30,000 and only 5,000 seats.

However, it was demonstrated that the city centre site could accommodate a multi- purpose stadium and arena seating up to 80,000 people, developed in manageable increments, in accordance with a strategy of building up the neglected fan-base. Since then, Newcastle United have followed a long-term business plan to reach a current capacity of 52,000 (filled for every league match), with scope for further development. There has been no ‘big bang’ and no ‘selling of the family silver’. The football club is a valuable part of the city centre.

There was a similar story in Cardiff, when the decision was being made to redevelop Cardiff Arms Park. Sites out of town alongside the M4 were promoted strongly, but the final decision to build the ‘Millennium Stadium’ in the heart of the city has been well and truly vindicated. As in Newcastle, it adds value to Cardiff City Centre.

A comparable development on the Liverpool Waterfront (such on the Clarence Dock site) or on Scotland Road (see below, paragraph 13b) could have the same effect. There are compelling reasons for Everton staying in the inner city or city centre.

10d. Twin Stadia: Dundee & Madrid

It seems strange to some people that there should be two similar stadia in a single city. But this is surely no more difficult to understand than there being two cathedrals or competing theatres and galleries.

In Madrid, the Estadio Santiago Bernabeu (home of Real Madrid) is situated on the city’s most prestigious street, the Castellana, alongside museums, ministries and mansions. The Estadio Vicente Calderón (home of Atlético de Madrid) is another large stadium on the banks of the River Manzanares, at the heart of a working-class district, a complete contrast to the Bernabeu. While building their new stadium, Atlético spent an unhappy year sharing the Bernabeu with Real.

In Dundee, the two clubs are practically next door to each other, within the same street. Dundee’s main stand is an attractive design by Archibald Leitch (designer of the historic structures at Goodison Park). Dundee United’s Tannadice Park is more modern and has a very different character. The relationship between the clubs is relatively friendly, but any suggestions that they should consider sharing a ground have been firmly rebuffed. 10e. Shared Stadium: Milan & Munich

Those who advocate a shared stadium point to the apparent success of such arrangements in the Italian cities of Milan, Turin, Genoa and Rome, where the stadium is typically built and managed with the active support of the municipality. In Milan, with its two giant clubs, AC Milan and Internationale, playing in the magnificent San Siro (Stadio Giuseppe Meazza), purpose-designed for football, this seems to work. In Turin and Rome, however, there is discontent. Juventus are reportedly unhappy with the arrangements at the Delle Alpi stadium (built by the City of Turin for the 1990 World Cup) which they share with Torino. There have been similar reports from Rome’s Olympic Stadium, which is shared by Roma and Lazio. However, the problem in these latter examples may be that they have to share non-football activities, particularly athletics, which compromise the stadium’s sight-lines and atmosphere.

Elsewhere in Europe, ground-sharing is unusual. The most significant example is in Munich, where Bayern and 1860 have combined to build a new arena, designed by Herzog and de Meuron (architects of Tate Modern and the Beijing Olympic Stadium). The building itself changes colour depending on which team is playing! However, Bayern are very much the senior partner in this venture. The situation in Liverpool is, of course, very different.

11. Optimum Seating Capacity and Quality

Most new seating areas should be built to better space standards, with a back-to-back depth of at least 800 mm, in contrast to older seats, where this can be as little as 660 mm. With improvements in seat width as well, the effective capacity is reduced by 25%. I recommend that, to retain essential atmosphere, the historic structures and other areas close to the pitch should retain the historic ‘congested’ standards (or return to ‘safe standing’ — but that’s another story). The new accommodation at the higher levels should be at ‘premium’ standards, reflecting the preferences of different groups of supporters, and being reflected in ticket prices.

It has been assumed that Everton require an initial capacity of at least 48,000, with the potential to expand this to an ultimate figure of 72,000. The options described below have been evaluated with these standards and figures in mind.

12. The Redevelopment of Goodison Park

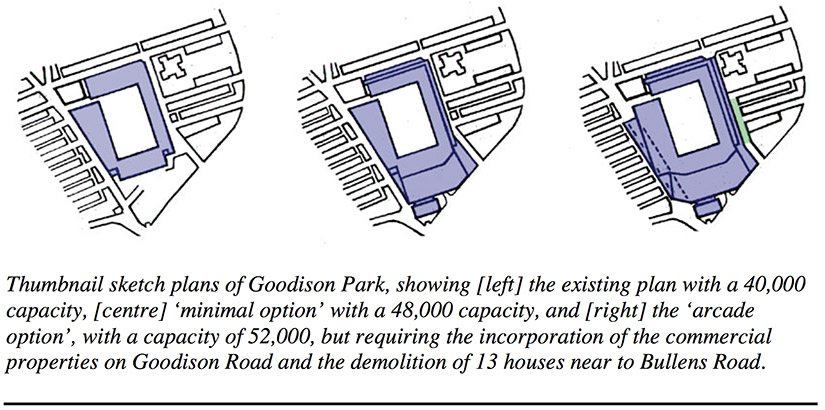

12a. The ‘minimum option’:

No change is not an option, but the first suggestion explores what can be achieved within the present footprint. This includes the car park behind the Park End Stand. It also includes Bullens Road, although does not require the demolition of any properties. Three tiers of ‘sky-boxes’ are proposed at the back of the Upper Bullens Stand and spanning the Gwladys Street stand, the latter sufficiently far forward to avoid further overshadowing of the street behind. These ‘sky-boxes’ would be part of a new roof structure that would eliminate the obstructed views from the upper tiers. The lower tiers would be reconfigured to remove the worst of the obstructed views without detracting from the valuable historic character of Archibald Leitch’s designs.

The restored Gwladys Street and Bullens Road stands could gain iconic status in World football and could be a fitting home to an International Museum of Stadium Design.

A new Upper Park End would be the maximum possible on the site, estimated at 7,000 assuming enhanced ‘premium’ space standards. Allowing for 2,000 seats in the Gwladys Street and Bullens Road sky-boxes but a loss of 1,000 seats in the re-design of the lower tiers, this would give a total capacity of 48,000.

A well-designed new Park Stand would be an appropriate immediate response to the building of the ‘New Anfield’ and could incorporate car parking (possibly a weekday park-and-ride facility) and commercial activity, with a landmark tower (possibly a hotel) on the corner of Walton Lane. It would be financed directly from the extra season tickets and lounge accommodation that it would incorporate, on the reasonable assumption that there is a demonstrable demand for 8,000 extra (unobstructed view, premium quality) seats and associated lounges.

12b. The ‘arcade option’:

This is an expansion of the ‘minimum’ solution, which includes forming an ‘arcade’ over Goodison Road, allowing a re-configuring of the Main Stand to improve seating space standards, lounges and other facilities, and to remove obstructed views. The capacity would rise to 52,000, with more than half of these at the ‘premium’ standard. At the same time, building over the full width of Bullens Road would allow for improved facilities. This would require the demolition of 13 houses (7 on Muriel Street and 4 on Diana Street).

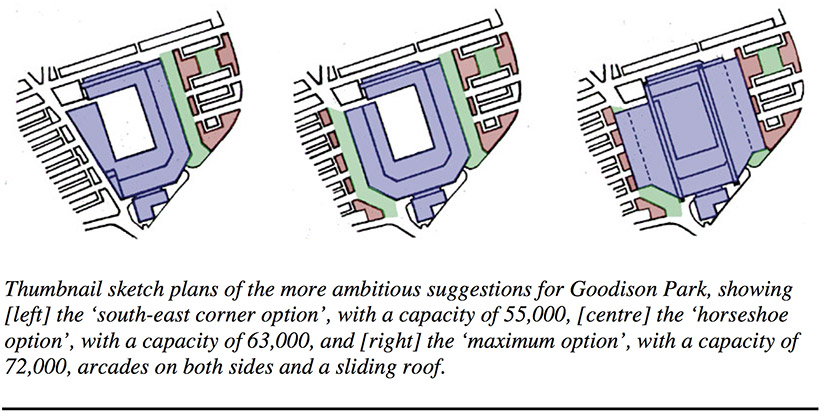

12c. The ‘south-east corner option’:This includes new stands above and behind the present Bullens Road and Park End Stands (see sketch plan below), with ‘sky boxes’ above Gwladys Street, a commercial tower on the corner of Walton Lane and car parking under the new Park End Stand. The school could be redesigned around an enclosed garden and enjoy a ‘partnership’ with some of the stadium facilities. Bullens Road would be widened and moved eastwards, requiring the demolition of 40 terraced houses.

12d. The ‘horseshoe option’:

This is the maximum proposed expansion of the stadium site, with the main stand being reconstructed in scale with the new Park End and Bullens Road stands.

It allows for long-term consolidation of the surrounding streets and the removal of future uncertainty and consequent blight. The total number of terraced houses to be demolished is 70. The new capacity would be 63,000.

12e. The ‘maximum option’:

This is a development of the ‘horseshoe’ to include a sliding roof and extra side tiers over arcades, bringing the capacity up to 72,000. This could be the best football ground in the world, and it would incorporate important elements of the historic character of Goodison. It may be a dream, but it is not unrealistic, if embedded within a consistent long-term plan with many phases.

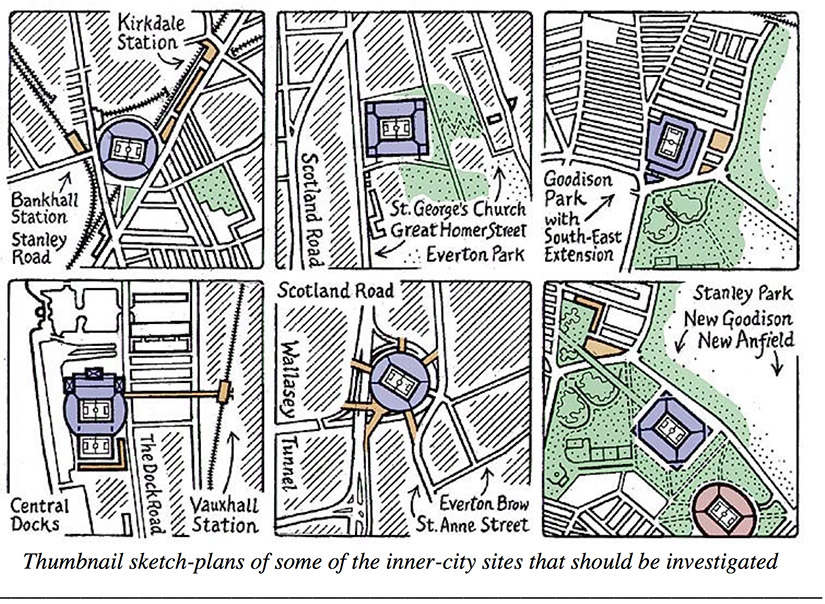

13. Some Alternative Sites in North Liverpool

13a. Everton Park

Given the club’s name and early history, this seems to be a particularly appropriate location, adjoining the proposed redevelopment of the centre of Everton (Project Jennifer). The present buildings of the Everton Park Sports Centre could be reconfigured and incorporated into the new development, which would also be able to accommodate other activities related to the community and the long-standing Great Homer Street Market.

The new stadium would become an integral part of Everton Park in the same way that the New Anfield will be part of Stanley Park. The two grounds would retain their historic proximity, with scope for joint initiatives in areas such as transport and tourism. The City Council has considered this site and considered it to be awkward, because of its slope. My view is that the slope provides opportunities to integrate different levels into the design, which could bring benefits in terms of both interest and economy.

13b. Scotland Road

The site is within the circle formed by the access road to the Kingsway (Wallasey) Tunnel. It is currently part-occupied by ‘Bestway’. It is large enough to contain a major football stadium in a tight circular structure, with circulation areas, parking and related commercial activity beneath the stands. Additional bridges would provide pedestrian access from six different directions. The site is only three-quarters of a mile from Lime Street and one-and-a-half miles from Goodison Park. Like the previous site, it adjoins the area of Project Jennifer. It could operate as part of the city centre, and could be a visually stunning addition to the northern approaches, as well as an exciting landmark viewed from Everton Park. It would have a minimal effect on its neighbours, being encircled by busy highways.

13c. Central Docks

This is the site of the former Clarence Dock Power Station. A stadium development could be combined with commercial development, including some very tall buildings, evoking the memory of the ‘three sisters’ (the chimneys which were prominent features of the Liverpool waterfront until their demolition). The stadium could be developed with a sliding roof and sliding pitch (overlooked by residential development), as in the earlier Kings Dock proposals. Direct public transport access could be provided from a new Vauxhall Merseyrail station.

As prospective developers of the Central Docks, Peel Holdings would have to be persuaded that a new stadium would be an asset within their vision of a high-quality high-density development. However, there are a number of new schemes in America, the Far East and Europe that could demonstrate this potential.

13d. Kirkdale

This is the triangle of railway land bounded by Stanley Road, Melrose Road, close to Kirkdale and Bankhall stations. The site is only three quarters of a mile from Goodison Park, and two miles from Lime Street. The superb Merseyrail links would make it suitable for weekday park-and-ride facilities and associated commercial activity, with the whole complex bridging the railway tracks.

13e. Stanley Park

There is a simple logic in considering a second stadium within Stanley Park, utilising the same methodology as the ‘New Anfield’ to extend the park into Walton via the present Goodison Park site. New development could be built on the Gwladys Street and Bullens Road frontages. Goodison Road would run alongside the new area of park, and greenery would be visible at the end of the streets leading up from County Road. A ramped bridge could provide a pedestrian link over Walton Lane. The ‘New Goodison’ (on the northern edge of the park) would match the ‘New Anfield’ in scale, but be in a contrasting style, possibly a stark rectangle rather than an ellipse. The expanded Stanley Park, with its two great stadia, their shared transport infrastructure and access, and the park’s historic structures protected and restored, would become an international tourist attraction, comparable with the two cathedrals in Hope Street.

14. Recommendations:

- To oppose any move from the inner-city.

- To pursue the preferred option of redeveloping Goodison Park.

- To bring Everton into a high-level task force involving the City Council and its public-sector partners, to secure the long-term development of both football clubs in the context of their respective communities in the north of Liverpool. This would include the two separate stadium developments, as well as joint initiatives on such matters as transport and tourism.